A new study has shed light on the early stages of planet formation through the examination of the V1298 system, which is approximately 30 million years old. Conducted by John Livingston from the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan and his co-authors, the research highlights a unique set of four planets, often referred to as “cotton candy” planets, due to their large size and low density. These findings were published in the esteemed journal Nature.

The V1298 system is located in the Taurus constellation, about 350 light years from Earth. In a fascinating comparison, if our Sun were likened to a middle-aged adult, V1298 would be a mere five-month-old infant. Despite its youth, it hosts four planets that are reminiscent of cotton candy, being approximately the size of Jupiter but significantly less massive. One of these planets, which is about five times the size of Earth, has a density comparable to that of marshmallows, while the least dense planet actually resembles cotton candy, with a density of only 0.05 g/cm2.

While astronomers have known about these planets for some time, this paper offers a crucial update on their mass estimates. Previous assessments suggested they were around 200-300 times heavier than the new findings indicate. This discrepancy arises from the youthful characteristics of V1298, which exhibits numerous sunspots and frequent flaring. These activities can obscure signals that researchers typically use to discover planets.

To obtain more accurate mass estimates, the team employed data from several telescopes, including Kepler, TESS, Spitzer, and the Las Cumbres Observatory, collected over a span of nine years. By utilizing a method known as transit-timing variations (TTVs), they monitored the timing of the planets transiting in front of their host star and corrected for gravitational interactions with nearby planets. This approach also allowed researchers to “recover” one planet that had previously eluded accurate orbital period determination, which is approximately 48.7 days.

Understanding the characteristics of these nascent planets offers insights into the broader context of exoplanet evolution. The study highlights two prevalent categories of exoplanets: “Super-Earths” and “Sub-Neptunes.” Super-Earths generally have a rocky composition and a radius less than 1.5 times that of Earth, while Sub-Neptunes are typically around 2.0 times Earth’s radius but are predominantly gaseous. Both types are often found in close orbits around their stars, even closer than Mercury in our solar system, likely because their rapid orbits are easier to monitor with telescopes.

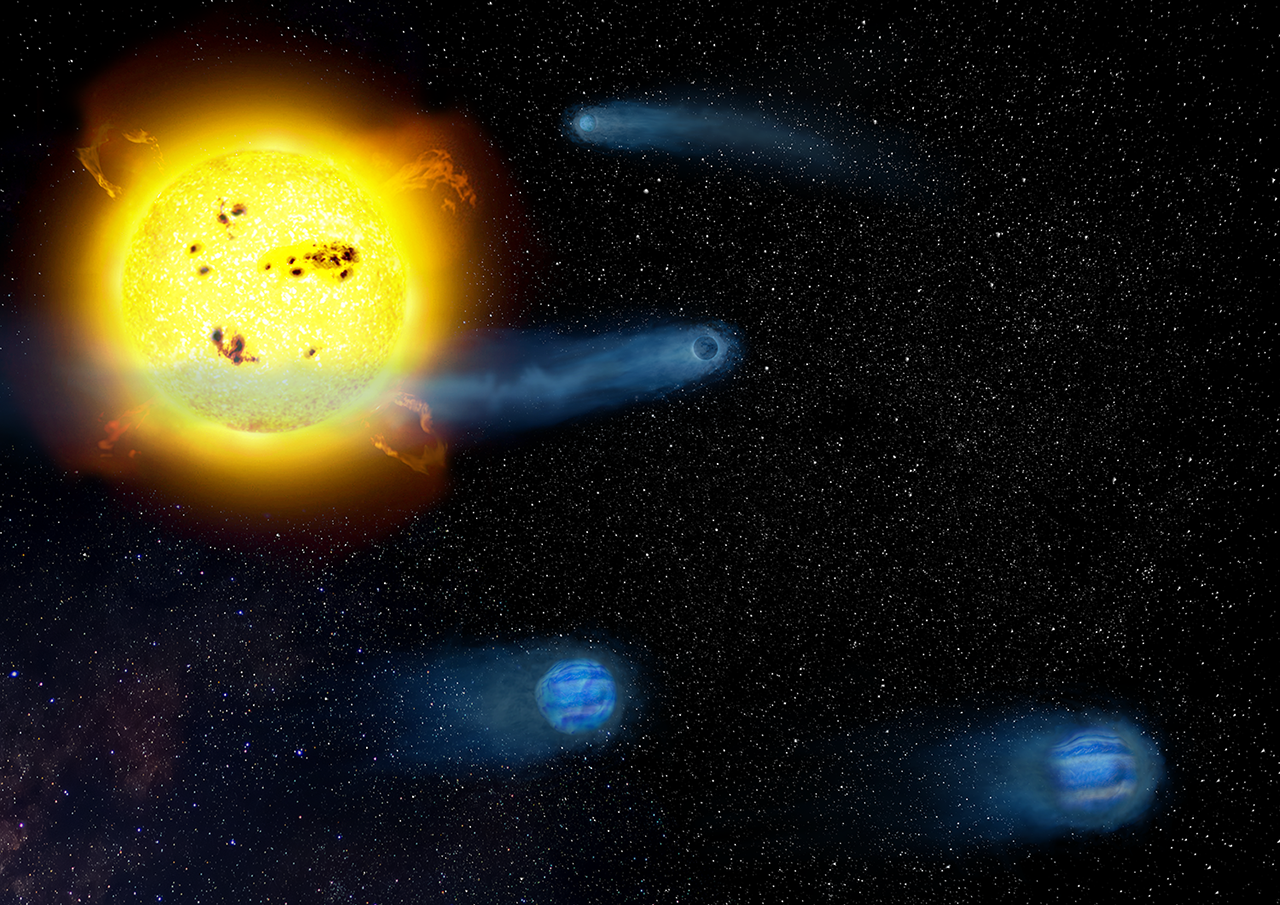

The diverse planetary system surrounding V1298 provides a model for how these two types of exoplanets can evolve in older, more established systems. Astronomers widely agree that as these planets mature, they will likely lose their atmospheres and shrink. This atmospheric loss is thought to occur through mechanisms such as photoevaporation, where radiation from the host star erodes the atmosphere, or through internal heat pushing the atmosphere away, a process that can span billions of years.

Interestingly, the study introduces a third process called “boil-off,” which may be significant in the early stages of planet formation. This occurs when the protoplanetary disk, which serves as a barrier to atmospheric pressure, is blown away, allowing the planet’s atmosphere to escape rapidly—similar to steam escaping from a pressure cooker when the lid is removed.

While the V1298 system is not the first to display these phenomena—another well-known example is Kepler-51, which is over ten times older—its youth offers invaluable insight into processes that may have already concluded in older systems. This research is particularly noteworthy for the extensive data collection that contributed to its findings, indicating that it may serve as a milestone in the study of exoplanets.

The implications of this research extend beyond V1298. There may be data from even younger star systems hidden within existing exoplanet datasets that could provide further clues to the mechanics of planetary formation. For now, the V1298 system stands as a compelling example of the complexities of planet formation and the evolution of celestial bodies in our universe.