A team of scientists from the U.S. Department of Energy’s Brookhaven National Laboratory has successfully engineered poplar trees to produce a key industrial chemical used in biodegradable plastics. This breakthrough, detailed in the Plant Biotechnology Journal on November 20, 2025, marks a significant advancement in sustainable materials production.

The modified poplar trees exhibit increased tolerance to high salt levels in soil, making them suitable for cultivation in less-than-ideal conditions. These trees can be broken down more easily, facilitating the conversion into biofuels and other bioproducts. This innovative approach not only aims to create a domestic supply chain for essential chemicals but also seeks to reduce reliance on imported alternatives.

Chang-Jun Liu, a biologist at Brookhaven, emphasized the potential of this research, stating, “This study demonstrates the metabolic ‘plasticity’ of poplar and the feasibility of engineering stress-resistant crops to produce multiple desired products.” Liu’s team collaborated with researchers from the Joint BioEnergy Institute and Kyoto University to achieve these results.

Re-engineering Poplar for High-Value Products

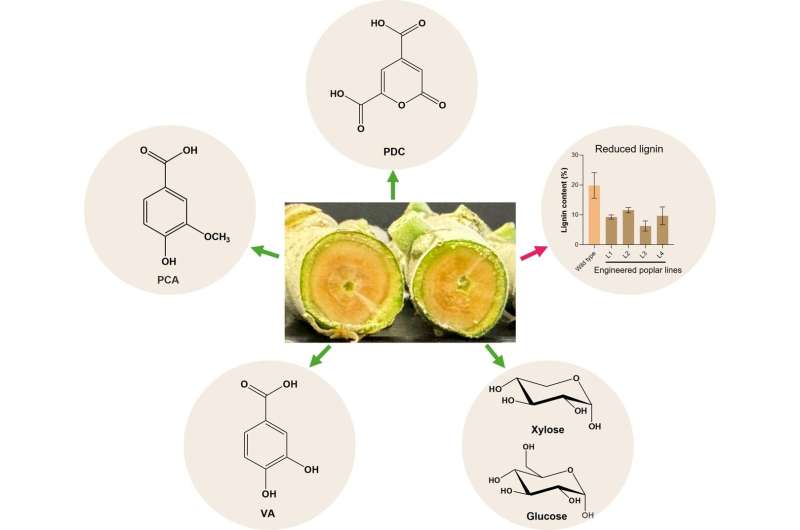

The research team focused on modifying hybrid poplar trees to produce 2-pyrone-4,6-dicarboxylic acid (PDC), a compound essential for creating durable plastics and coatings. Traditionally, PDC is produced through complex chemical processes or microbial breakdown of biomass. By inserting five genes from naturally occurring soil microbes into the trees, the scientists established a synthetic metabolic pathway that enables the plants to generate PDC and other valuable compounds.

Nidhi Dwivedi, a member of Liu’s team, pointed out the advantages of using poplar for this purpose. “Poplar grows quickly, adapts to many environments, and is easy to propagate,” she explained. The addition of the new metabolic pathway significantly broadens the range of bioproducts these trees can produce.

Enhancements and Future Applications

The genetic modifications not only facilitated PDC production but also altered the internal chemistry of the poplar trees. The engineered plants exhibited lower levels of lignin, which typically complicates biomass breakdown, while their hemicellulose levels increased. This change resulted in a yield of up to 25% more glucose and 2.5 times more xylose, both of which are vital ingredients for biofuels and other products.

Additionally, the modifications led to higher concentrations of suberin, a waxy substance that serves protective functions for the plant. This enhancement allows the trees to thrive in challenging environments, including soils with high salinity. Dwivedi noted, “These trees can grow on soil not suitable for food production, so they won’t compete for prime agricultural land.”

At this stage, the findings are based on greenhouse-grown plants. The next phase involves testing the engineered poplars in field conditions to assess their performance and stability over time. The research team aims to optimize the metabolic pathway further to increase yields of PDC and related compounds.

This model for plant-based manufacturing is adaptable and can be scaled to meet varying demands without the substantial investment typical of traditional chemical manufacturing facilities. Liu concluded, “Using different combinations of genes, we can potentially make additional products. This knowledge will help researchers design productive crops for a range of U.S. manufacturing and agricultural needs.”

The implications of this research extend beyond biodegradable plastics, offering a promising avenue for sustainable materials and energy production. As scientists continue to explore the genetic capabilities of plants, the potential for innovative solutions in addressing environmental challenges grows.