Engineers at Purdue University have proposed a groundbreaking approach to designing lunar landing pads using local materials. In a recent paper published in Acta Astronautica, led by Shirley Dyke, the team explores how to construct durable landing pads from lunar regolith, addressing the challenges posed by the Moon’s unique environment and the logistics of transporting materials from Earth.

The need for structured landing pads stems from the potential hazards associated with landing large rockets on the lunar surface. Although spacecraft like SpaceX’s Starship could theoretically land on any flat area, the intense force from retrograde rockets can dislodge rocks and dust, which poses a risk to both the craft and any nearby infrastructure, such as future lunar bases. As such, mission planners advocate for the development of a dedicated landing pad, akin to those used on Earth.

Building a landing pad on the Moon presents unique challenges. The cost of shipping concrete from Earth is prohibitively high, making it essential to utilize the local regolith. The properties of this lunar soil remain largely unknown, particularly how it behaves when sintered—a process that can create a strong, cohesive structure. Dr. Dyke emphasizes the necessity of in-situ testing, as simulants cannot replicate the Moon’s specific conditions.

Understanding Mechanical and Thermal Properties

The design of a lunar landing pad must take into account its mechanical and thermal properties. The team has attempted to estimate the structural characteristics of sintered regolith based on existing literature, hypothesizing that this material may be weaker in tension than in compression. Furthermore, sintered regolith is expected to be thermally insulative, which means that the top layer may heat significantly during a rocket’s launch, leading to potential cracks each time a craft ascends.

The lunar environment adds another layer of complexity. The Moon experiences extreme temperature fluctuations over its 28-day lunar cycle, which could cause the landing pad to expand and contract. This thermal stress, coupled with friction from loose regolith beneath the pad, may lead to additional complications such as warping and cracking.

The authors recommend that for a landing craft weighing 50 tons, the landing pad should have a thickness of approximately 0.33 meters (or 14 inches). Dr. Dyke explains that increasing the pad’s thickness could inadvertently increase the likelihood of thermal fracture, countering the goal of creating a durable structure.

Future Testing and Implementation

One of the major concerns surrounding the design is the phenomenon known as spalling, where chips of the pad break off due to thermal expansion and contraction. This degradation could reduce the pad’s ability to support heavy landing vehicles over time. The potential for fracturing from thermal stresses or improper landing angles remains a significant risk.

To address these uncertainties, the research team advocates for systematic in-situ testing during early lunar exploration missions. These missions could gather crucial data about the regolith and its properties under actual lunar conditions. Dr. Dyke is particularly interested in monitoring how the landing pad deforms under load and during temperature extremes.

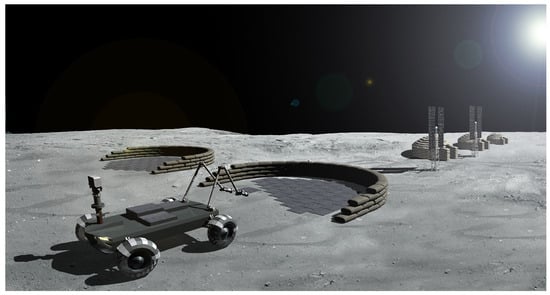

Ultimately, the construction and maintenance of the landing pad are expected to rely heavily on robotic technology. Given the challenges posed by human labor in space, especially in bulky space suits, autonomous or teleoperated robots will play a vital role in both building and maintaining the landing infrastructure.

As NASA and other space agencies work towards returning astronauts to the Moon, the insights gained from this research may inform future designs for safe and effective lunar landing pads. The iterative process of testing and refining these designs could lead to robust structures that facilitate extended human exploration of our closest celestial neighbor.