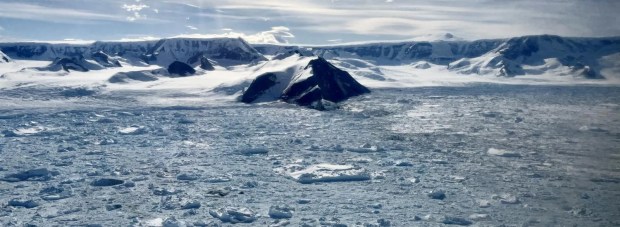

A team from the University of Colorado Boulder has identified a process responsible for the unprecedented retreat of the Hektoria Glacier in Antarctica, which lost approximately half of its mass in just two months. The glacier, which is grounded on bedrock, retreated about 15.5 miles between January 2022 and March 2023, marking the fastest observed retreat for any grounded glacier.

Research Affiliate Naomi Ochwat noted the glacier’s rapid retreat during her monitoring of Antarctic glaciers. The team aimed to understand the mechanisms behind this extraordinary loss of ice. Ochwat emphasized the importance of this discovery, stating, “This process, if it could occur on a much larger glacier, then it could have significant consequences for how fast the ice sheet can change as a whole.”

Despite its relatively small size—about 8 miles across and 20 miles long—the Hektoria Glacier’s retreat poses potential implications for sea level rise, although the immediate impact is minimal, contributing only fractions of a millimeter. Senior Research Scientist Ted Scambos explained that understanding this process could reveal other areas in Antarctica at risk of similar rapid retreats.

The glacier’s stability relied on fast ice, which supports its ice tongue—a section of ice that extends into the ocean. As warmer conditions led to the detachment of this fast ice, the floating ice tongue began to break apart. Scambos clarified that while this breakdown is not unusual, what is remarkable is the behavior of the glacier resting on its underlying ice plain, a flat area of bedrock below sea level.

As the incoming water thinned the glacier, it caused the ice resting on the bedrock to rise, leading to increased water pressure underneath. This resulted in large slabs of ice breaking off, a phenomenon described by Scambos as similar to “dominoes falling over backwards.” Ochwat noted, “The thing that’s important, though, is this mechanism, this ice plain that thins and starts to float and causes a rapid retreat. That process hasn’t been seen before.”

The study revealed that the glacier’s rapid retreat was primarily driven by this calving process rather than by atmospheric or oceanic conditions. Using satellite-derived data, the researchers observed the glacier’s changes in elevation and surface area. Their findings indicate that glaciers resting on ice plains can be easily destabilized, raising concerns about the broader implications for the Antarctic ice sheet.

Historically, Antarctic glaciers with ice plains have experienced rapid retreats, sometimes retreating hundreds of meters per day 15,000 to 19,000 years ago. This context helps in understanding the current dynamics of the Hektoria Glacier. Scambos remarked, “It meant this grounded glacier lost ice faster than any glacier had in the past,” highlighting the urgency of identifying other areas in Antarctica that could undergo similar transformations.

The potential for significant sea level rise remains a critical concern, as ice sheets store vast amounts of water. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, nearly 30% of the U.S. population lives in coastal regions vulnerable to flooding and erosion due to rising sea levels. Globally, eight of the ten largest cities are situated near coastlines, as noted by the United Nations.

Ochwat concluded by stressing the global relevance of the research, saying, “What happens in Antarctica does not stay in Antarctica, and that’s why it’s really important to research these things because there’s so much we don’t know and so much that could have profound effects for us.” The team’s findings underscore the need for continued investigation into the factors influencing glacier behavior in a warming world.