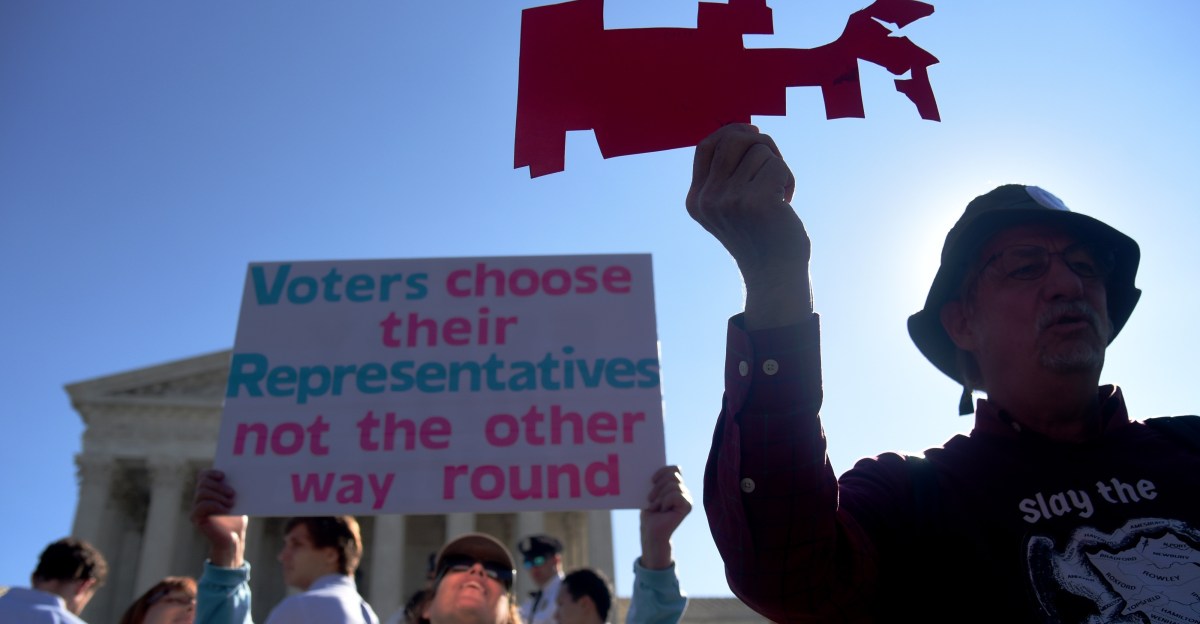

The Supreme Court has upheld a Texas gerrymander that is projected to provide Republicans with an additional five seats in the United States House of Representatives. This decision, announced on November 18, 2025, reverses a previous ruling by a lower federal court that deemed the gerrymander unconstitutional. The ruling in the case of Abbott v. League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) highlights the deep partisan divisions within the Court, with the justices voting predominantly along party lines; only the three Democratic justices dissented.

The implications of the LULAC decision extend beyond Texas, posing significant challenges for future federal lawsuits aimed at contesting gerrymandered electoral maps. Legal experts suggest that the stringent burden placed on plaintiffs may deter many from pursuing cases against gerrymandering, as the likelihood of success appears increasingly slim.

Understanding the context of LULAC requires recognition of the two primary types of gerrymandering: partisan and racial. Partisan gerrymanders are designed to benefit the political party in power, while racial gerrymanders aim to manipulate district lines based on racial demographics. The distinction is crucial, as past Supreme Court decisions have treated these two forms of manipulation differently.

In the landmark case of Rucho v. Common Cause (2019), the Court’s majority ruled that federal courts cannot intervene in disputes over partisan gerrymanders. As a result, maps drawn with partisan intent are often upheld, regardless of their impact on voter representation. The Court has also imposed barriers to plaintiffs challenging racial gerrymanders, with expectations that it will further weaken protections under the Voting Rights Act in the near future.

Before the LULAC decision, there was a glimmer of hope for those challenging racial gerrymanders. The Court had ruled in Alexander v. South Carolina NAACP (2024) that if race played a predominant role in redistricting, such maps would face heightened scrutiny. However, the recent ruling appears to undermine this precedent.

The situation in Texas illustrates the complexity of gerrymandering cases. The Justice Department under former President Donald Trump had previously pressured Texas to redraw its electoral maps, claiming it was illegal for a state to create districts where white voters were in the minority. This letter laid the groundwork for the gerrymandered maps at the heart of the LULAC case. The lower court’s decision to strike down these maps was based on substantial evidence suggesting that racial considerations influenced their design.

Despite the lower court’s findings, the Supreme Court’s ruling in LULAC criticized the lower court for failing to presume legislative good faith. The majority opinion emphasized that courts should interpret ambiguous evidence in favor of the state, which could further complicate future challenges to gerrymandering.

In a notable turn, the Court’s majority also criticized the plaintiffs for not proposing a viable alternative map that met the state’s partisan objectives. This requirement implies that to contest a racial gerrymander, plaintiffs must create a map that fulfills the same political goals without appearing racially biased. Such a condition could prove nearly impossible, particularly in cases where maximizing partisan advantage inherently diminishes minority representation.

The ruling also raised concerns about the timing of the lower court’s decision, with the majority suggesting it altered election rules close to an election. However, this assertion is factually inaccurate, as the lower court’s ruling occurred nearly a year before the upcoming midterm elections.

In conclusion, the LULAC decision represents a significant step towards cementing gerrymandering practices in the United States. With the Supreme Court’s Republican majority signaling a reluctance to intervene, the ability of voters and civil rights advocates to challenge partisan or racial gerrymandering appears severely restricted. The cumulative effect of these new burdens on plaintiffs suggests that only the most compelling evidence will suffice to challenge gerrymandered maps in the future.