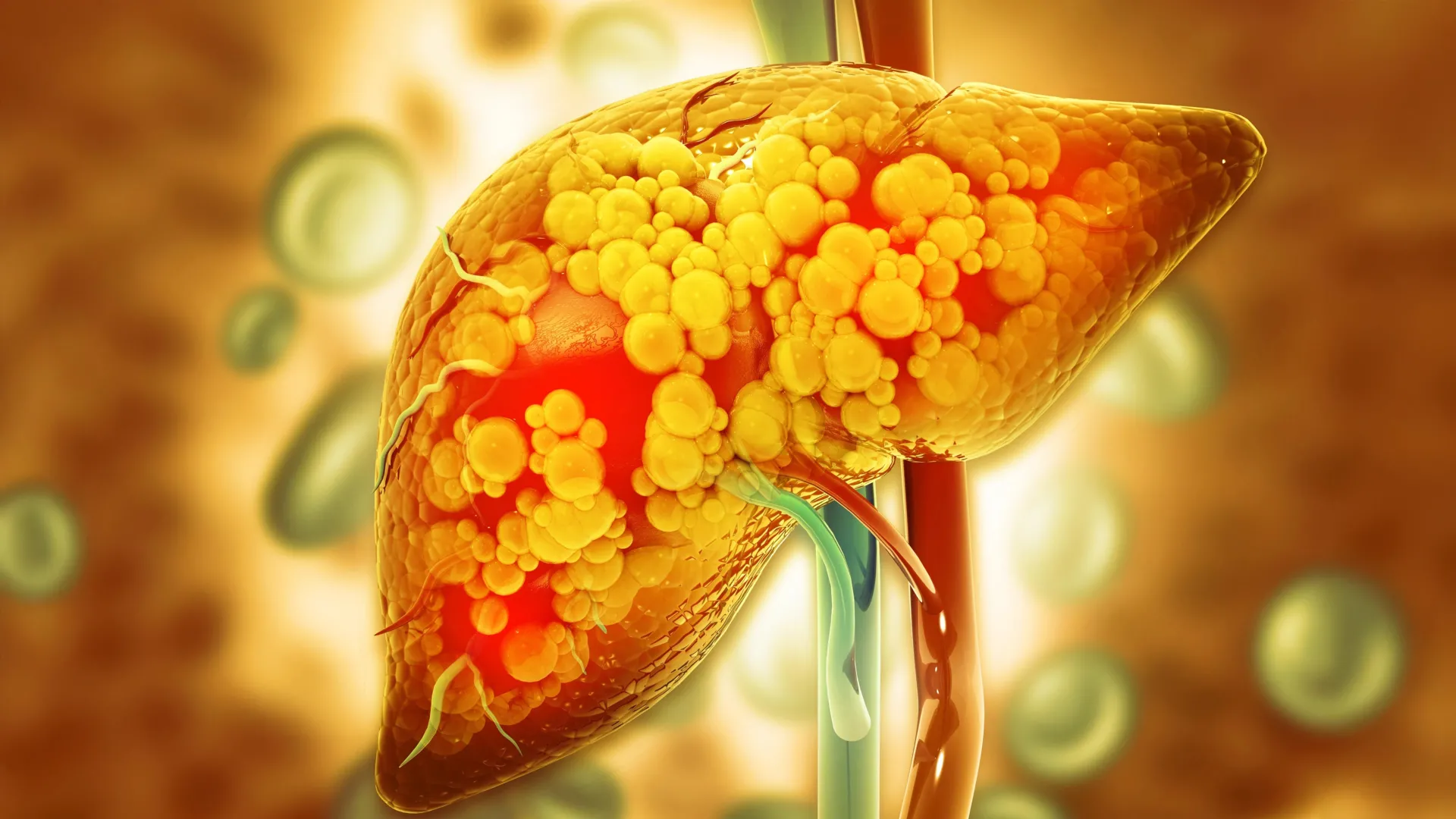

Research conducted at the University of Oklahoma has revealed a promising link between a natural gut compound and the reduction of fatty liver disease in offspring. The study, published on February 8, 2026, suggests that the compound, known as indole, produced by beneficial gut bacteria, may significantly mitigate the risks associated with poor maternal diets high in fat and sugar during pregnancy.

Children whose mothers consume unhealthy diets while pregnant and breastfeeding are at an increased risk of developing fatty liver disease later in life. The findings indicate that administering indole to pregnant and nursing mice can lead to healthier liver outcomes for their offspring, potentially altering the trajectory of liver health into adulthood.

Understanding the Role of Indole

The research team, led by Jed Friedman, Ph.D., director of the OU Health Harold Hamm Diabetes Center, and Karen Jonscher, Ph.D., associate professor of biochemistry and physiology, aimed to investigate the microbiome’s influence on the development of fatty liver disease. They found that indole, which is generated when gut bacteria metabolize tryptophan—an amino acid present in foods like turkey and nuts—can provide protective benefits against metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD).

“Unfortunately, the risk is higher if a mother is obese or consumes a poor diet,” Dr. Friedman noted. The prevalence of MASLD in children is concerning, with rates at approximately 30% among those with obesity and about 10% in non-obese children.

Study Findings and Future Implications

The study involved female mice fed a high-fat, high-sugar diet throughout pregnancy and lactation. Some of these mice received indole, while others did not. After weaning, the offspring were placed on a standard diet before transitioning to a Western-style diet to promote the development of fatty liver disease.

Results showed that offspring born to mothers who received indole exhibited numerous health advantages, including healthier liver function, reduced weight gain, and improved blood sugar levels. Additionally, these mice maintained smaller fat cells despite exposure to an unhealthy diet later in life. Notably, the researchers observed activation of a protective gut pathway involving the acyl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR), contributing to these positive outcomes.

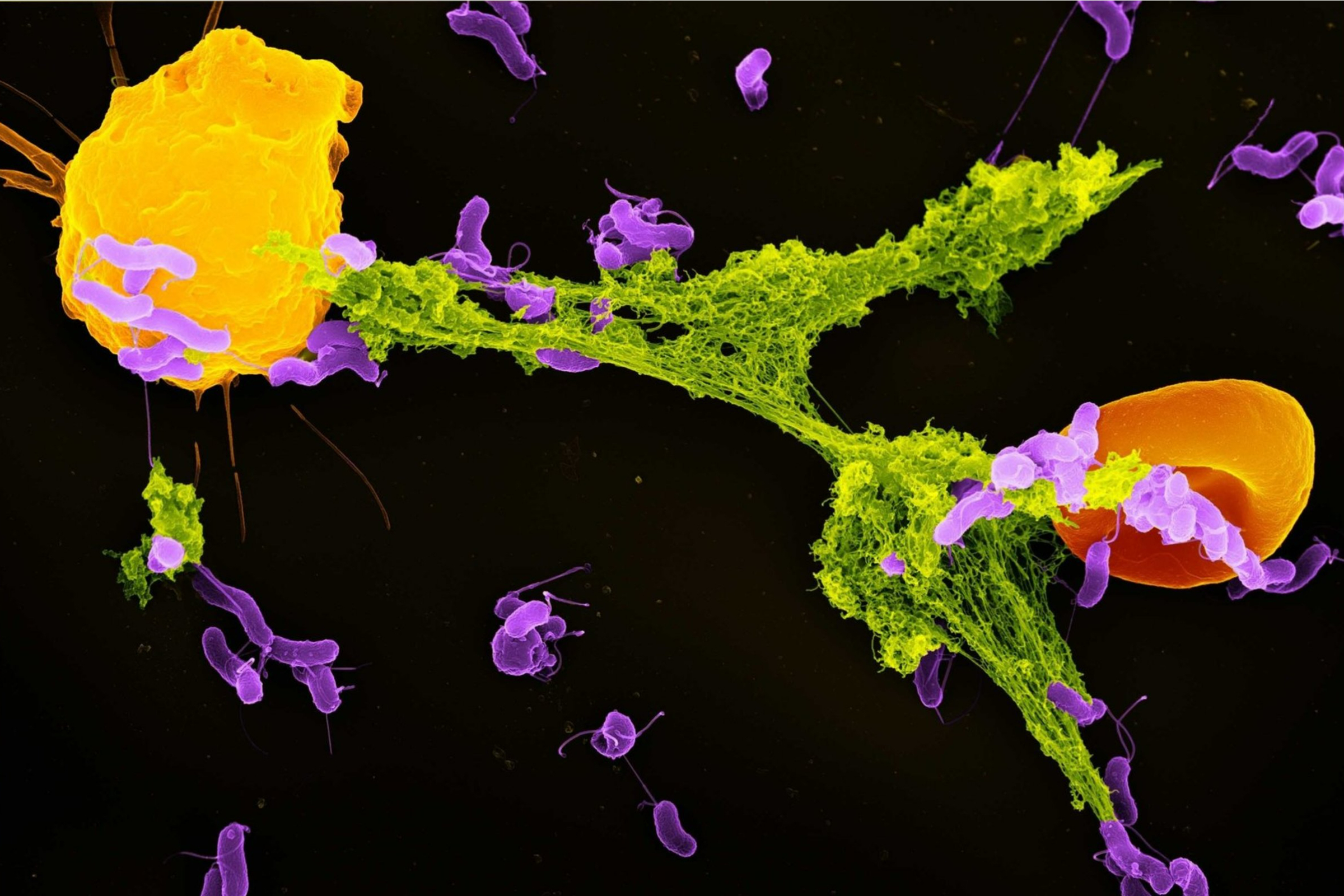

In a compelling experiment, gut bacteria from the protected offspring were transplanted into other mice that had not received indole. These recipient mice also demonstrated reduced liver damage, underscoring the microbiome’s crucial protective role.

While these findings were derived from animal studies, they open the door to new preventive strategies against childhood MASLD. Currently, effective treatment options for pediatric MASLD are limited, with weight loss being the only recognized intervention once the disease is established.

“Anything we can do to improve the mother’s microbiome may help prevent the development of MASLD in the offspring,” Dr. Jonscher stated. The implications of this research suggest that enhancing maternal gut health could play a vital role in reducing the incidence of liver disease in future generations.

As the study advances our understanding of the relationship between diet, gut health, and liver disease, it highlights the importance of maternal nutrition and its long-term effects on child health. The research team’s findings point toward the potential for early intervention in combating the rising incidence of MASLD among children.