A groundbreaking study led by the University of Auckland has shed light on the evolutionary origins of one of nature’s earliest motors, which facilitated movement in bacteria approximately 3.5 billion to 4 billion years ago. Researchers have developed an extensive understanding of bacterial stators—protein structures analogous to pistons in a car engine—essential for mobile life forms.

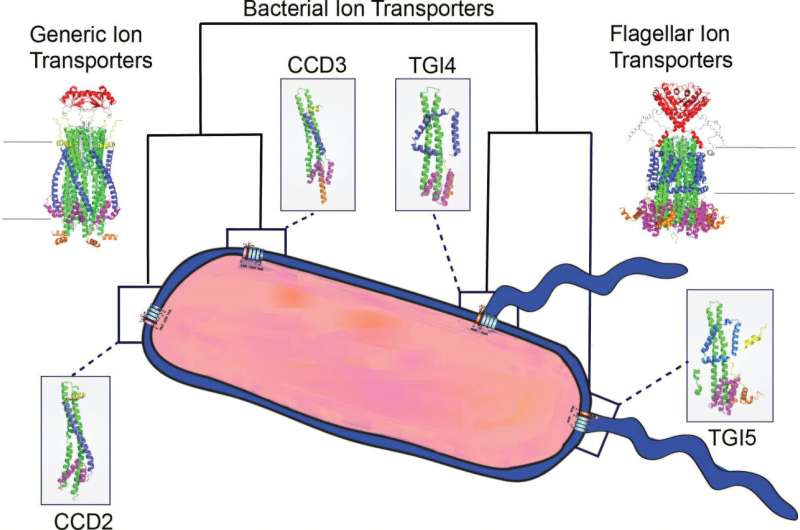

Dr. Caroline Puente-Lelievre from the School of Biological Sciences explained that stator proteins are embedded in the bacterial cell wall. They convert charged particles, or ions, into torque, enabling bacteria to propel themselves through liquid environments. This research, published in the journal mBio, highlights how movement is integral to all forms of life, from microscopic organisms to larger animals.

Unraveling the Mechanics of Ancient Bacteria

The collaborative research, which involved institutions such as UNSW Sydney and the University of Wisconsin Madison, leveraged the advancements of DeepMind’s AlphaFold. This AI technology, introduced in 2020, predicts the three-dimensional structures of proteins, facilitating deeper insights into bacterial movement.

During Earth’s early days, characterized by intense volcanic activity and meteorite bombardments, bacteria emerged as single-celled organisms equipped with sophisticated internal motors. These stators generate the power necessary to turn a rotor, which in turn spins the flagellum—a long appendage that propels the bacteria through their environment, functioning much like a microscopic propeller.

To examine these stators, researchers analyzed genomic data from over 200 bacterial genomes. They constructed evolutionary trees, utilized advanced computational tools, modeled 3D protein structures, and conducted laboratory experiments to validate their findings. The specific three-dimensional shape of each protein is vital, as it directly influences function.

Tracing the Evolution of Stator Proteins

The study involved predicting the sequences and structures of ancestral proteins that may have existed millions or billions of years ago. “We aimed to reconstruct how these proteins evolved,” Dr. Puente-Lelievre noted. A typical stator consists of five identical MotA proteins and two identical MotB proteins. According to Dr. Nick Matzke, the senior researcher at the University of Auckland, these motor proteins evolved from a simpler two-protein system that later diversified into various functions.

Matzke emphasizes that complex biological machines often develop by repurposing simpler mechanisms. Just as the ancestors of birds likely adapted protofeathers for different uses, ancient bacteria transformed a basic ion flow tool into a powerful engine for movement.

In their research, the team compared the three-dimensional structures of proteins to identify significant differences and specific traits unique to stators, such as regions responsible for generating torque. “Functional assays in the lab confirmed that the torque-generating interface is essential for movement in E. coli,” Dr. Puente-Lelievre stated.

Despite billions of years of evolutionary changes, the core features of these microscopic engines have remained remarkably consistent, underscoring their importance in sustaining life.

“We are witnessing a remarkable era for structural biology and microbiology,” said Assistant Professor Matthew Baker from UNSW Sydney. “With the discovery of new sequences and tools like AlphaFold, we can efficiently explore potential protein structures.”

This research not only illuminates the origins of bacterial motility but also opens new avenues for understanding the complexities of early life forms on Earth. The insights gained from this study may have implications for various fields, from evolutionary biology to biotechnology, highlighting the enduring significance of these ancient biological mechanisms.

For further details, refer to the study by Caroline Puente-Lelievre et al, titled “Evolution and structural diversity of the MotAB stator: insights into the origins of bacterial flagellar motility,” published in mBio on November 11, 2025.