Researchers at New York University have made a groundbreaking discovery by examining fossilized bones that date back between 1.3 million and 3 million years. They uncovered thousands of preserved metabolic molecules, which provide a unique glimpse into the diets, diseases, and climates of ancient animals. This innovative approach is set to significantly enhance our understanding of prehistoric ecosystems.

For the first time, scientists successfully analyzed metabolism-related molecules preserved within these ancient bones. This research reveals insights not only about the animals themselves but also about the environments they inhabited. The findings, published in the journal Nature, indicate that these regions were once much warmer and wetter than they are today.

The study’s lead researcher, Timothy Bromage, a professor of molecular pathobiology at NYU College of Dentistry, expressed his excitement about applying metabolomics to fossil studies. “I’ve always had an interest in metabolism… It turns out that bone, including fossilized bone, is filled with metabolites,” Bromage stated. This research could transform how scientists reconstruct ancient ecosystems, moving beyond traditional DNA analysis.

Preserved Chemistry in Fossils

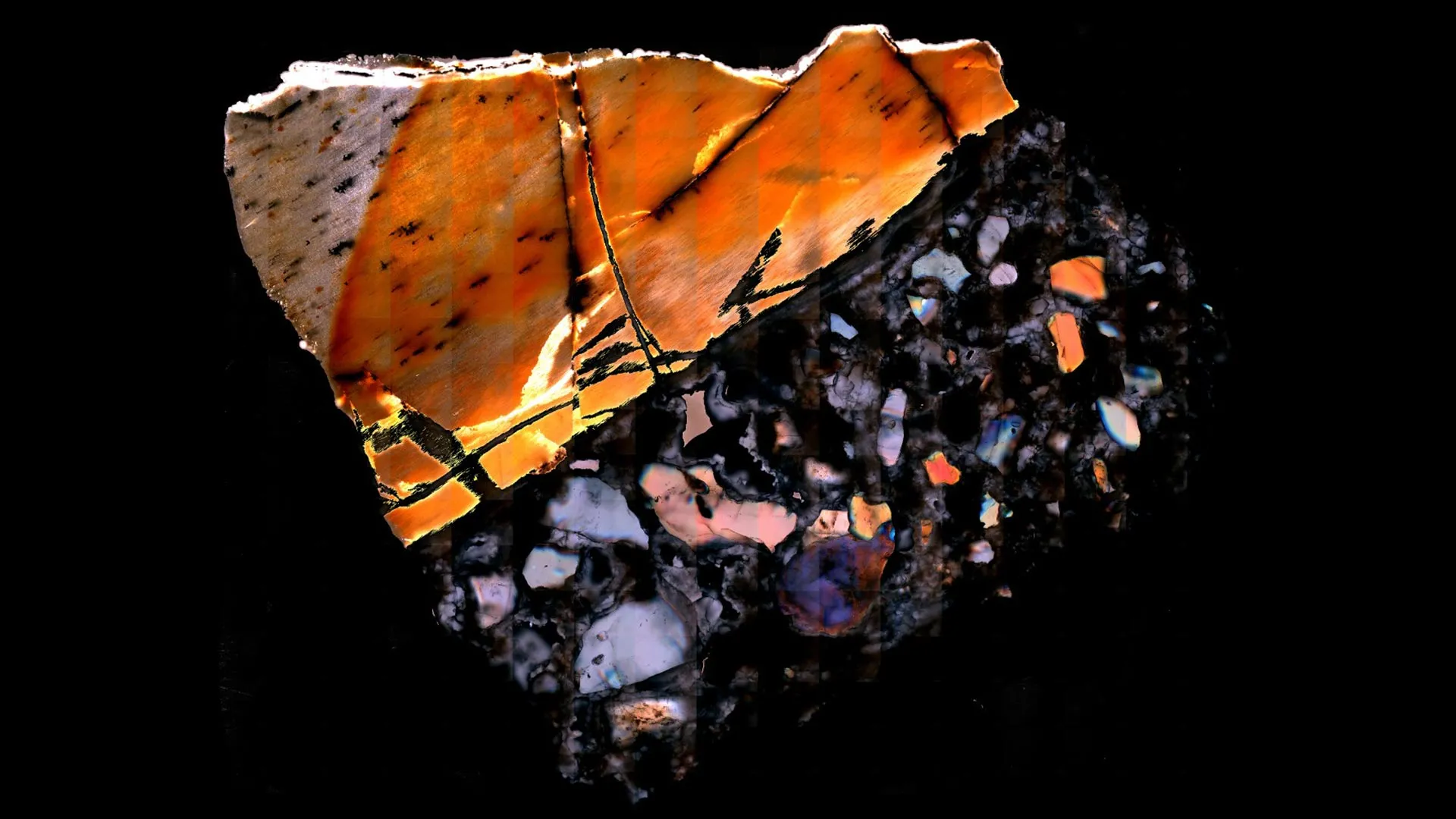

Recent advances in understanding fossilized materials have shown that collagen, a key structural protein, can survive in ancient bones, including those of dinosaurs. Bromage noted that if collagen could be preserved, then other biomolecules might also remain intact. He proposed that during bone growth, metabolites circulating in the blood could become trapped within the microscopic spaces of bone, potentially remaining preserved for millions of years.

To validate this theory, the research team employed mass spectrometry, a technique that identifies molecules by converting them into charged particles. Tests conducted on modern mouse bones revealed nearly 2,200 metabolites. This method was then applied to ancient animal bones excavated from sites in Tanzania, Malawi, and South Africa, known for their significance in early human history.

The fossils examined belonged to various species, including rodents like mice and ground squirrels, as well as larger animals such as antelopes, pigs, and elephants. The analysis revealed thousands of metabolites, many of which corresponded closely to those found in modern relatives of these animals.

Insights into Health, Diet, and Environment

The metabolites identified provided valuable information about the biological processes of these ancient animals, including their diets and potential health issues. Some chemical markers indicated the presence of female animals, while others revealed signs of disease. A notable example involved a ground squirrel bone from Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania, dated to approximately 1.8 million years ago. This bone exhibited evidence of infection from the parasite responsible for sleeping sickness, caused by Trypanosoma brucei, which is transmitted by tsetse flies.

Bromage elaborated on this finding, stating, “What we discovered in the bone of the squirrel is a metabolite that is unique to the biology of that parasite… We also saw the squirrel’s metabolomic anti-inflammatory response, presumably due to the parasite.” These findings not only shed light on the health challenges faced by these ancient creatures but also illustrate how they interacted with their environments.

Furthermore, the research team was able to trace the diets of these animals based on the metabolites linked to specific plants. Although the database for plant metabolites is less comprehensive than that for animals, the researchers identified compounds associated with regional flora, including aloe and asparagus. Bromage explained, “Because the environmental conditions of aloe are very specific, we now know more about the temperature, rainfall, soil conditions, and tree canopy.”

The reconstructed habitats align with existing geological and ecological studies, suggesting that the fossil evidence consistently points to climates that were significantly wetter and warmer than those observed today. “Using metabolic analyses to study fossils may enable us to reconstruct the environment of the prehistoric world with a new level of detail,” Bromage concluded.

The research team included authors from various departments within NYU, such as Bin Hu, Sher Poudel, Sasan Rabieh, and Shoshana Yakar, along with collaborators from institutions in France, Germany, Canada, and the United States. The research received financial support from The Leakey Foundation, with additional assistance for scanning electron microscopy provided by the National Institutes of Health.

This innovative application of metabolomics to the study of fossils opens new avenues for understanding ancient life and ecosystems, potentially revolutionizing the field of paleobiology.