Recent research indicates that cosmic rays generated by supernova explosions may significantly influence the formation of Earth-like planets. A study led by Ryo Sawada at the University of Tokyo reveals that these cosmic rays could produce essential radioactive elements, such as aluminum-26, which are thought to play a pivotal role in the development of rocky planets like Earth.

For years, scientists have theorized that the early solar system was enriched with radioactive materials from the remnants of a nearby supernova. This enrichment was believed to contribute to the formation of water-depleted rocky planets. However, the traditional explanation posited an unlikely scenario: the supernova had to explode at an ideal distance—close enough to deliver radioactive material, yet far enough to avoid catastrophic destruction of the protoplanetary disk. This rare alignment raised questions about the feasibility of Earth’s formation.

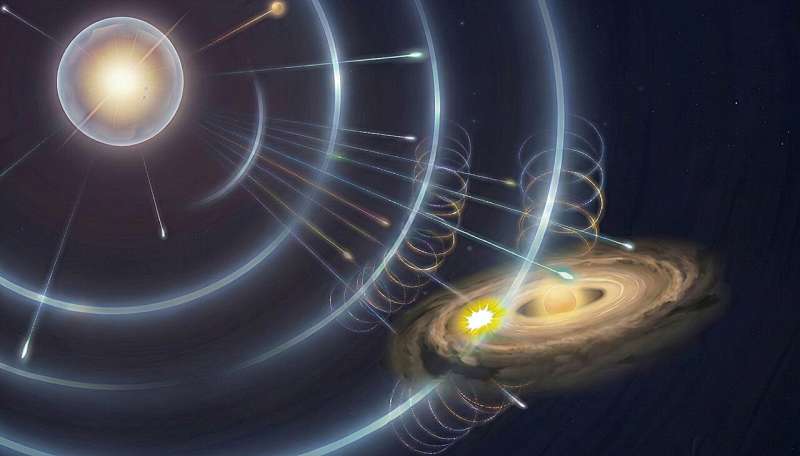

In the course of his research on supernova physics and cosmic rays, Ryo Sawada found this explanation to be lacking. He noted that supernovae are not merely destructive events; they also act as powerful particle accelerators. The shock waves from these explosions generate vast quantities of high-energy particles known as cosmic rays, which can extend far beyond the initial explosion.

In a paper published on December 21, 2025, in the journal Science Advances, Sawada and his colleagues conducted numerical simulations to explore the effects of cosmic-ray interactions with the protosolar disk. They discovered that these interactions can initiate nuclear reactions that produce crucial short-lived radioactive elements, including aluminum-26, at distances of approximately one parsec from a supernova. Such a distance is common in star clusters where many sun-like stars form.

The findings suggest that the young solar system may have been surrounded by a “cosmic-ray bath,” rather than relying on an unlikely direct injection of materials from a supernova. This mechanism offers a more universal explanation for the origins of Earth-like planets. If cosmic-ray baths are prevalent in stellar nurseries, the processes that shaped Earth could be more common than previously thought.

The implications of this research extend beyond the formation of Earth. If the presence of cosmic rays and their resulting chemical processes are typical, then the conditions conducive to forming rocky planets may exist around a significant number of sun-like stars. This challenges the notion that Earth-like planets are rare or that their formation relies on extraordinary circumstances.

While the study does not imply that every habitable planet results from such cosmic events, it does provide a fresh perspective on planetary formation. Factors such as disk lifetime, cluster dynamics, and stellar interactions still play critical roles in the development of habitable worlds.

Sawada’s research underscores the interconnectedness of astrophysical processes. He emphasizes that understanding cosmic-ray acceleration can illuminate questions about planetary science and habitability. The study serves as a reminder that sometimes the key to comprehending our origins lies in recognizing what has been overlooked in previous models.

This work adds to the growing body of literature exploring the dynamic relationship between supernovae and planetary formation. As scientists continue to investigate these cosmic phenomena, the potential for new discoveries about the universe and our place within it remains vast and compelling.